The word ‘History’ without any problematisation is fraught with conceptual and epistemological difficulties. The breaking of the word ‘history’ into two syllables ‘his’ and ‘story’ is not only male-centric or androcentric, but a reflection of the selectivity and biases associated with history. Following the invention of writing, human beings shifted from the pre-industrial practice of storing and transmitting received knowledge through orality to literature. The shift from oral culture to literary culture affected the discipline of history. Until the invention of writing and later the printing press, human beings had collective ownership of history. Stories were created to enjoin group solidarity, as well as enforcing didactic values.

The introduction of writing and the printing press has had an enduring effect on human beings. Writing has encouraged individualism, by breaking the collective ownership of history. Individuals, therefore, construct history reflecting their idiosyncrasies, whims, and caprices. While literary culture predated the intrusion of Arabs and Europeans in the lives of Africans, focusing on Egypt and Ethiopia, modern literary culture in much of so-called Black Africa is one of the enduring legacies of colonialism. Colonialism, thus, presaged the marginalisation of some aspects of African history by the early nationalists. Taking a cue from colonial historiography, which focused on what the colonialists constructed as important and worthy of documentation, many African historians in the 1960s focused on the ‘big’ things of the flow of events in Africa. They focused on politicians, chiefs, religious leaders, and rebels. This pushed some of the unsung heroes into obscurantism. Certainly, this is the tragedy of social history in much of Africa.

Today (July 17, 2019) was a good day because it marked one of the attempts to break the mental chains of Euro-centric historiography about Africa by an accomplished Ghanaian historian, Prof. De-Valera NYM Botchway of the University of Cape Coast, UCC (affectionately known as either University of Competitive Choice or University of Commendable Casfordians). He launched his book, Boxing is no cakeway: Azumah ‘Ring Professor’ Nelson in the Social History of Ghanaian Boxing. The book masterfully departs from the legacy of European historiography of Africa by focusing on Azumah Nelson, who moved from the margins of life to the core of it. The transition of Prof. Azumah from the periphery to the core of life, from urban slum to a global icon is emblematic of the fruit of hard work, honesty, and humility. It is the case of success chasing excellence!

At about 11 years, my generation in Zongos got to know about Azumah Nelson. We would stay deep into the night to catch a glimpse of most of his ‘gladiator savviness’. While my generation never watched the fight between Azumah Nelson and Wilfredo Gómez Rivera, the Puerto Rican former professional boxer and three-time world champion, on December 8, 1984, we constructed any fierce fight in Maamobi as one of ‘Azumah vs Gómez’. His pugilistic abilities astounded most of us! We could easily relate to Azumah because he emerged from a ‘backwater’ community to the epicentre of the world. It was, therefore, a delight to have met him and listened to the metanarrative about his life today. His life embodies a fusion of fate and faith.

What became the highlight of the book launch was the screening of short videos of Azumah’s professional life. One of the videos that showed Azumah Nelson brandishing the flag of Ghana, while saying repeatedly, ‘I am a Ghanaian and I am proud of Ghana and Africa’. In 2008, the Ghanaian ethnomusicologist and former head of the Department of African Studies (now Centre of African and International Studies), Prof. N.N. Kofie, remarked that African boxers, particularly Azumah Nelson, are more courageous than African scholars. In other words, the ring professor, Azumah Nelson, is more diligent and consistent in defending his national pride than Ghanaian scholars. Indeed, boxing is a game that provides an arena, where racism is temporarily neutralised. In the philosophy of Nelson Mandela of South Africa, who was an amateur boxer, the ring provides a ‘raceless’ space for people of all social and political backgrounds to demonstrate strength, wit, and agility.

In the ring, boxers are made to defend their pride and lay claim to bragging right regardless of their nationalities or ‘racial’ backgrounds. It is within the locus of this logic that Azumah Nelson demonstrated pride in Ghanaian and African cultures. It was in the ring that he taught people of other races that the African could not be despised without the attending menacing consequences. He deconstructed the myth of the superiority of Europeans. Thus, through Azumah’s invincibility, he challenged the provincialising of Europe. Given the remarkable achievement of Azumah, when he was invited to give his remarks as the special guest of honour of the book launch, he used the expression, ‘my fellow professors’ to refer to the classroom professors in the auditorium. Immediately, there was thunderous laughter and applause. Did the classroom professors accept the inclusion of Azumah into their social network?

Since the introduction of modern university to Africa by Europeans in the twentieth century, many African scholars have risen through the academic ladder to occupy important positions in the ivory tower. Attempts have been made to bridge the gap between the town and gown. But it appears that after about six decades of the introduction of the modern university in Africa, the continent has not made marked progress in overcoming the colonial legacies of underdevelopment. The continent of Africa is still faced with gapping challenges such as poor sanitation and squalid living conditions, abject poverty, deprivation, diseases, and political instability. The modern university in western Europe was philosophically positioned to research, as opposed to the pre-modern era of the university serving as the storehouse and the transmitter of ‘conventional’ knowledge. The focus of the modern university is to research and to proffer solutions to the predicaments of the continent.

Certainly, African scholars are publishing, because of the logic, ‘publish or perish’. But in most cases, they are more of producers of data than analysts of data. Just like the peasant farmer, who supplies raw materials to the industrial west, most African scholars are more of consultants than researchers who provide raw data to the west. African scholars are, therefore, consumers of western theories, rather than the creators of their theories. It has almost become axiomatic that any African postgraduate student must provide a theoretical or conceptual framework in the course of their writing. Impliedly, every postgraduate student in Africa must cite western scholars to validate their (African postgraduate students) research.

Additionally, Africa’s ‘accomplished’ scholars must also publish with western journals and publishers before their academic writings could be baptised and initiated into the world of intellectuals. Western academics have always set the standards for African scholars to sheepishly follow. There is no intellectual independence in Africa. Indeed, not yet uhuru for African scholars! And since knowledge production is as well a political project, westerners have always determined the kinds of knowledge that Africans produce. In sum, westerners are the gatekeepers of knowledge. This situation is such that, for any African to receive tenure-ship or promotion in African universities, the African scholar must provide a list of international journals he/she has published with. In other words, he must show how much of the west he has parodied. Also, it is sad that even when Africans are writing about themselves, they must beg for endorsement from the west! Given this sorry situation of African scholars, is it any wonder that one of Africa’s burdens is epistemic injustice?

Epistemic injustice is more dangerous than any form of oppression. This is precisely because in the twenty-first century the rulers of the world are the possessors of information. The world is heading to the tipping point of digital dictatorship, which is informed by the monopolisation of information.

What is going to be the contribution of Africans to a world where resources have shifted from material endowment to knowledge/information endowment? Will Africa ever rock the boat or rub shoulders with the west and east in the production of knowledge? Will Ghanaian scholars be as courageous and determined as Azumah Nelson to challenge the epistemic injustice inscribed on the psyche of Africans? Will they be able to show that brain is as important as the brawn?

The life and times of Ring Prof. Azumah Nelson is a challenge to classroom professors. Until African scholars hold the bull by the horn to develop confidence in themselves and their publishing institutions, the continent will remain the scum of the earth. Until there is a real u-turn, Africa will continue to be a repository of racialised western epistemology. This is hard to write, but it is a sad reality. We cannot continue to pay lip service to publish in Africa. We must trust our guts and ability to produce quality. Until then, we must heed the Baganda proverb that, ‘A borrowed water does not quench thirst’.

Satyagraha

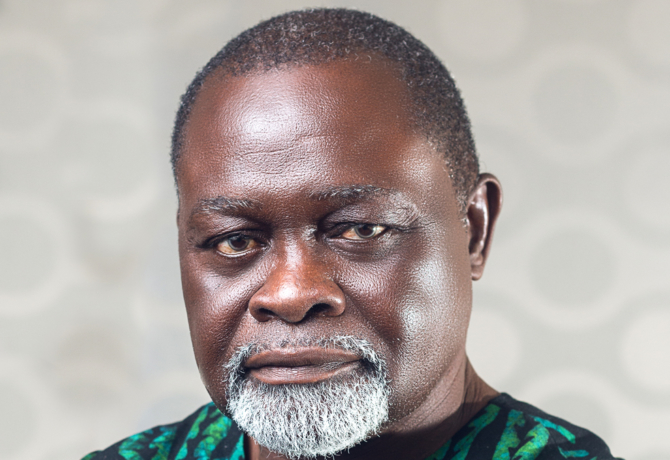

Charles Prempeh (prempehgideon@yahoo.com), African University College of Communications, Accra

What do you think about this piece? Share your comment in the comment thread and share the story using the social media buttons above. You may reach the editor on 0249579664. Thank you.